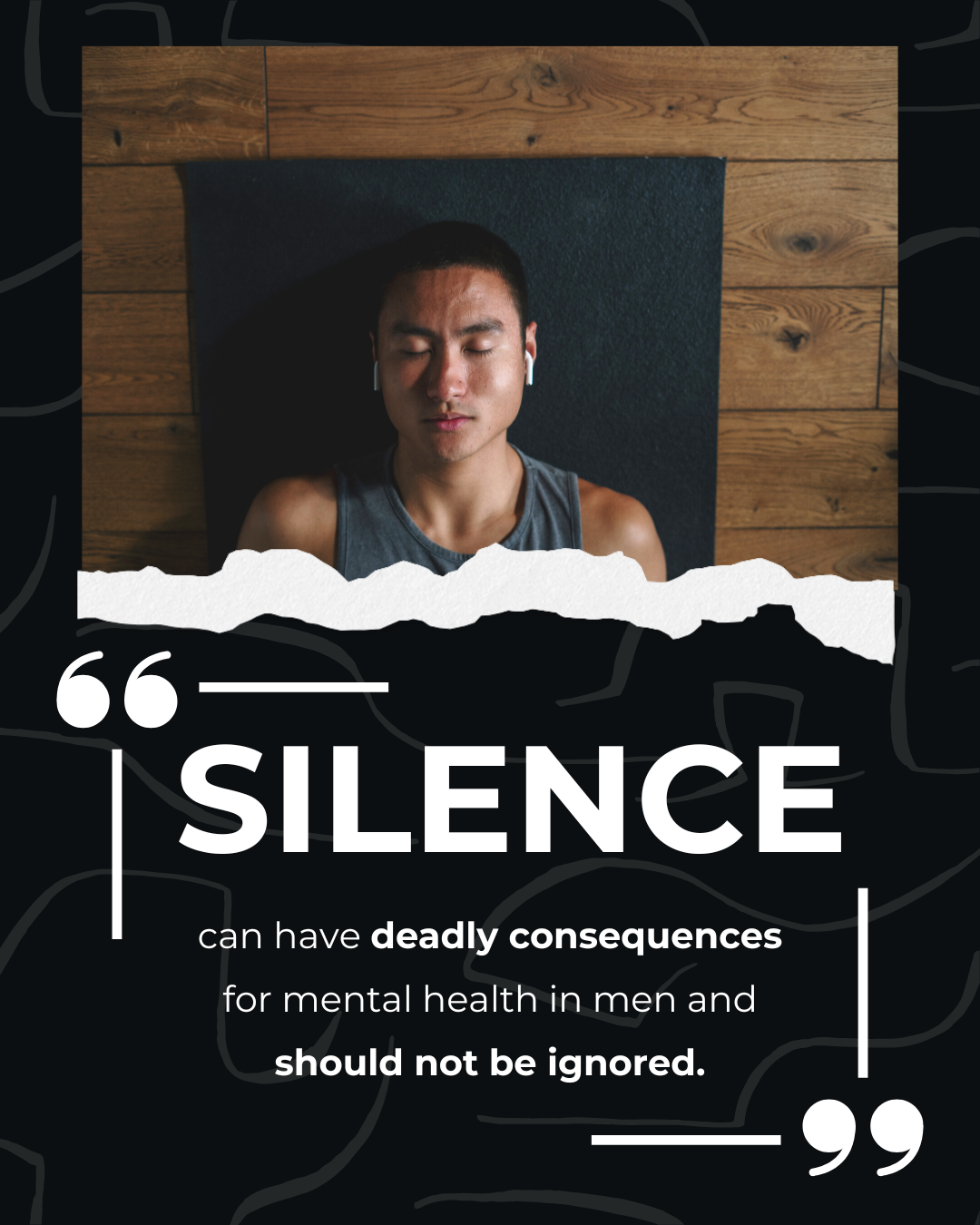

While suicide continue to be a leading cause of mortality among men worldwide, despite the worsening increase in loss of men’s lives, it is still often referred to as the ‘silent epidemic’. This silence, and the experiences of being silenced, is primarily linked to the way in which boys and men were socialized from a young age according to traditional masculine norms – particularly dominance, stoicism, power, strength and self-reliance, all of which influence the silencing of men.

In the context of men’s mental health, this silence manifest in different ways. For one, men become reluctant to disclose distress or seek help of out of fears of being seen as weak, both by themselves and other people. To that end, this reluctance is also a way for men self-isolate as a way to protect themselves from being ‘othered’ due to the gender-transgressing nature of being vulnerable and needing help. In addition, silence also results from the shame men experience – stemming from a sense on inadequacy or failure to conform to societal expectations for being a man, as well as the stigma associated with mental illness (both from the society and internalized self-stigma). Lastly, this distinct silence also manifests in men’s lack of representation in crucial empirical studies of psychopathology and mental illness – a problem that means that we continue to poorly understand men’s mental illness including their susceptibility to self-harm and suicide, and potential recovery strategies.

As a part of moving forward, society needs to collectively work to reshape cultural masculinity norms, reduce stigma around mental illness, normalize help-seeking among men and develop gender-transformative interventions that would be highly responsive to men’s specific and diverse needs. Among others, this include transforming the ways in which boys are socialized in their early developmental years, change the way we discuss mental health and masculinities in public, and work on programs and initiatives with the goal of improving men’s mental health outcomes. Peer support is also crucial for men to be able reframe help-seeking as a strengths-based practice, while still being able to embody some masculine capital around helping and supporting others. That way, men might be more motivated to help other men, while also responding to their own mental health needs in a way that aligns with normative masculinities. Lastly, there is still more work to be done to develop, test and disseminate psychological treatments for men – for instance, gender responsive training that foster greater openness among clinicians and trainees in the healthcare setting.

Click here to read the full article